If you are reading this then it is likely that you know of Abraham-Louis Breguet’s pocket watch No. 160 Grande Complication aka the ‘Marie Antoinette’ and its place within the annals of watchmaking. From the watchmaker whose pocket watches made appearances in a literary fiction of the time, it has become not just arguably the most famous pocket watch to date, but also a news-headliner whose (mis)adventures even formed a central part of an international bestseller – Allen Kurzweil’s ‘The Grand Complication’ (2001), as well as decades worth of international headlines.

As was standard practice for the period, the No. 160 was the result of a commission, in 1783. The definitive ‘who’ of the order, something which historically has been of great import (and recorded) in Breguet (brand and the watchmaker’s) early history, has become almost incidental in the pocket watch’s modern history, as is the fact that despite being known as the ‘Marie Antoinette’, she was long dead before the timepiece was ever completed, although it was ostensibly commissioned as a gift for her.

Given its size and complications – the request was for all the horological complications possible at the time, within the context of both what she was known to prefer and the nature of women’s timepieces of the period (e.g. it is 63mm in diametre and complicated), if it was indeed intended for Marie Antoinette, the No. 160 was probably not ordered to be used so much as a display of both horological skills and the devotion of the client.

Thanks to the Breguet archives (sidebar about the advantages that material archives have in terms of ease of access and longevity which outlasts digital) although there is no record of the order itself, there is some information about the order, but not enough to complete the story of this larger-than-life timepiece. Not only expansive (the complications) in order and price (it had no budgetary limits), it took decades to complete, covering pre and post the Revolution, Abraham-Louis’ exile to Switzerland and return to Paris, and was not completed until 1827, three years before Abraham-Louis Breguet died. It is signed ‘Breguet et fils’ to note the involvement of his son Antoine-Louis.

A timepiece of 823 parts, Abraham-Louis Breguet’s No. 160 has a clear crystal dial onto which there are markers for the time, date of the month, day of the week, month, 48-hour power reserve, temperature via a bi-metallic thermometer, and equation of time. Beneath it you can see the movement responsible for the ‘grand complications’ of a perpetual calendar with leap year correction, dead seconds/ second hand that acts as a stopwatch, and minute repeater.

Given the passage of time from order to completion, the No. 160 ended up remaining with Breguet, with its first recorded owner the Marquis de la Groye, followed by numerous people and appearances at public exhibitions until the twentieth century and point at which the story of its modern fame comes in.

The watch was purchased in 1917 by collector Sir David Lionel Salomons, who was a member of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers (whose museum resides at the Science Museum). Upon his death his daughter Vera Bryce Salomons donated his collection to what is now known as the Museum for Islamic Art (previously called the L.A. Mayer Institute for Islamic Art) which she founded. The No. 160 was not the only Breguet timepiece in the collection, which included dozens of clocks by the watchmaker.

There it sat until April 1983 when it was stolen in an audacious mass theft of 106 timepieces, several paintings, and books. Allen Kurzweil, as mentioned earlier, alludes to this night in this interview about ‘The Grand Complication’. The thief climbed through a narrow window, cut holes in the display cases and departed with 100 watches, several paintings and books.

The thief was never caught.

In 2004 then Swatch Group CEO Nicolas Hayek recruited Breguet’s watchmakers to build a replica of the No. 160, using a combination of archival material and photos. Completed in 2008, it took on the reference of No. 1160, and you can read about it here.

In an example of rather spectacular coincidental timing, in 2006, as the No. 1160 was still underway, a Tel Aviv watchmaker contacted the Museum, saying that he recognised some clocks for which he had been asked to provide a valuation, as those which had been stolen in 1983. You can read the contemporary account of the discovery in this Haaretz article. The Museum then received a phone call from lawyer Hila Efron Gabbai, who said that she was representing an unnamed client who was interested in negotiating the return of thirty-nine of the 106 stolen timepieces in exchange for payment. The client said that she had discovered them in her husband’s effects. The Museum agreed to pay NIS 150,000. Her dead husband was revealed be Na’aman Dieler (Diller), a notorious thief in the 1960s to 1970s.

“Diller had entered through a window in the back. He’d used a hydraulic jack to widen the metal bars and had managed to get inside with the help of a rope ladder,” said Sgt.-Maj. Oded Yaniv who headed the team investigating the case that was reopened in 2007.

The alarm system was not functioning at the time.

Following the return of the watches the museum redeveloped its clocks and watches gallery, with adeqyate security.

Now the No. 160, whose nickname has taken over its origins, is taking a trip abroad to form part of exhibition with a theme covering the period of its (nick) namesake. The Museum for Islamic Art is lending watch to the Science Museum in London to form part of its ‘Versailles: Science and Splendour’ exhibition, which looks at the evolution of science at the Palace of Versailles through the reigns of Louis XIV, Louis XV and Louis XVI through over 100 objects.

The exhibition runs from December 12, 2004 until April 21, 2025. Tickets cost £12, with free entry for children aged 11 and under. You can read about the exhibition at this link and buy tickets online here.

For an in-depth look at the No. 160’s story, you can read ths paper and this link.

In a bit of circularity, as it were, a storm struck Versailles in 2005, knocking down Marie Antoinette’s oak tree that stood outside of the Petit Trianon. Breguet purchased the fallen oak and used the wood to create the marquetry box in which No. 1160 is housed. This purchase helped to fund work at Petit Trianon, including restoration of its interior.

The No. 1160’s box has more than 3,500 pieces reproducing the parquet flooring at the Petit Trianon. Inside, more oak was used to depict the hand of Marie-Antoinette holding a rose. Who ordered it, who it was intended for – these no longer matter, as its history and profile has transcended that order in 1783.

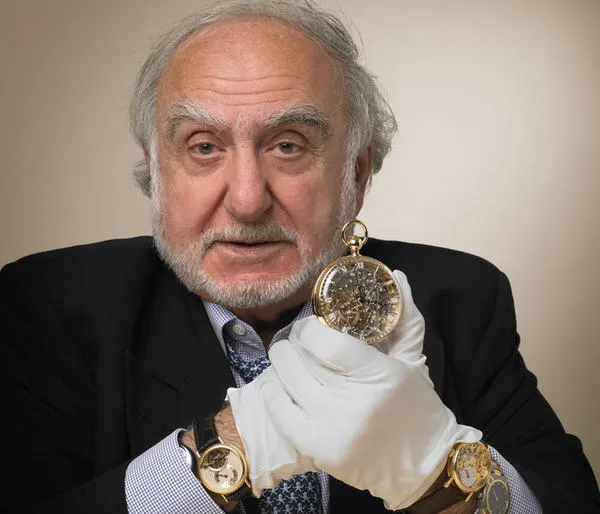

[Photo credit: The Museum for Islamic Art, Jerusalem and Breguet]

Categories: Breguet, Ephemera, London, Minute Repeaters, pocket watches

Thanks very interesting thanks for sharing

LikeLike